|

WORKING PAPER

Combatting Institutional Blindness: How Companies Can Illuminate the Futureby Stephen Wunker, David Farber, and Jessica Wattman

|

|

INTRODUCTION–A WORLDOF VOLATILITY

Volatility in the marketplace is keeping executives up at night. A recent survey of U.S. CEOs found that 86% believe that advances in technology will transform their businesses over the next five years. Another 60% think that new market entrants will threaten their growth prospects.1 Such anticipated turmoil creates an urgent demand to see what the future may hold.

Unfortunately, most companies lack a systematic framework for generating insights about the future in a consistent and reliable way. With each new product or service (which we will lump together as “products” for short), they scramble to predict emerging trends, figure out how old customer data can be used, and tie in known benchmarks about the competitive landscape. The result is often a lackluster reception for a promising new product, leaving companies baffled as to what went wrong and struggling to find a fix. These companies suffer from what we call institutional blindness, an ignorance about context that leads to taking inappropriate risks, missing key trends, and developing competitive vulnerabilities.

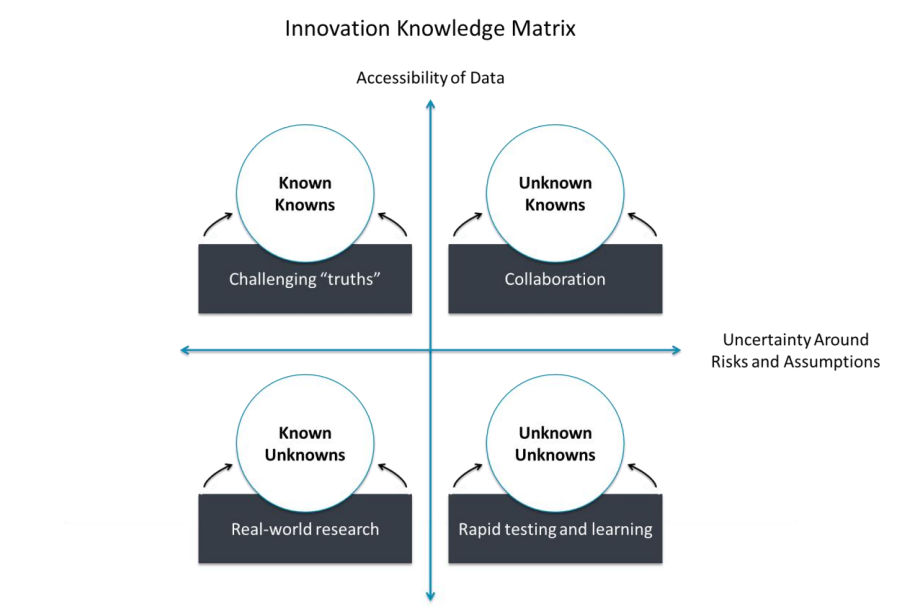

Fortunately, institutional blindness is an organizational dysfunction with a fairly straightforward fix, as shown through the Innovation Knowledge Matrix (IKM) that we introduce here. The IKM emerged from a five-year process of cataloguing what companies think they know and what leads them to become disconnected from emerging realities. It shows how companies can combat tunnel vision, unchecked assumptions, and other forms of institutional ignorance.

THE DANGERSOF INSTITUTIONAL BLINDNESS

We have found that institutional blindness leads to four broad dangers, each of which relates to a distinct quadrant of blindness in the IKM.

1. Missing new market opportunities. Companies often focus too closely on their core business, relying heavily on in-hand data and past strategies as a compass for the future. As a result, they miss opportunities to venture into adjacent new markets at critical times. When Crumbs Bake Shop launched in 2003, there were only three bakeries devoted to cupcakes in the United States.2 Over the next few years it began a modest, but successful, expansion beyond its New York roots. But by 2011, things had changed, and there were hundreds of cupcake shops crowding the market. Nevertheless, Crumbs continued to rely on the success of existing stores as proof that it could orchestrate a massive expansion. It focused on adding more stores – stretching to 65 locations at its peak – without devoting sufficient attention to growth opportunities for existing stores. Its only new products were those that were more likely to cannibalize existing sales than boost the average ticket size, and even these new offerings did little to expand the company beyond a saturated and shrinking cupcake market. The company was executing its existing offerings well, but competition and changing consumer priorities were quickly shifting its context. In July 2014, as same-stores sales continued to decline and costs climbed, the company – by then the world’s largest cupcake company – failed.

Volatility in the marketplace is keeping executives up at night. A recent survey of U.S. CEOs found that 86% believe that advances in technology will transform their businesses over the next five years. Another 60% think that new market entrants will threaten their growth prospects.1 Such anticipated turmoil creates an urgent demand to see what the future may hold.

Unfortunately, most companies lack a systematic framework for generating insights about the future in a consistent and reliable way. With each new product or service (which we will lump together as “products” for short), they scramble to predict emerging trends, figure out how old customer data can be used, and tie in known benchmarks about the competitive landscape. The result is often a lackluster reception for a promising new product, leaving companies baffled as to what went wrong and struggling to find a fix. These companies suffer from what we call institutional blindness, an ignorance about context that leads to taking inappropriate risks, missing key trends, and developing competitive vulnerabilities.

Fortunately, institutional blindness is an organizational dysfunction with a fairly straightforward fix, as shown through the Innovation Knowledge Matrix (IKM) that we introduce here. The IKM emerged from a five-year process of cataloguing what companies think they know and what leads them to become disconnected from emerging realities. It shows how companies can combat tunnel vision, unchecked assumptions, and other forms of institutional ignorance.

THE DANGERSOF INSTITUTIONAL BLINDNESS

We have found that institutional blindness leads to four broad dangers, each of which relates to a distinct quadrant of blindness in the IKM.

1. Missing new market opportunities. Companies often focus too closely on their core business, relying heavily on in-hand data and past strategies as a compass for the future. As a result, they miss opportunities to venture into adjacent new markets at critical times. When Crumbs Bake Shop launched in 2003, there were only three bakeries devoted to cupcakes in the United States.2 Over the next few years it began a modest, but successful, expansion beyond its New York roots. But by 2011, things had changed, and there were hundreds of cupcake shops crowding the market. Nevertheless, Crumbs continued to rely on the success of existing stores as proof that it could orchestrate a massive expansion. It focused on adding more stores – stretching to 65 locations at its peak – without devoting sufficient attention to growth opportunities for existing stores. Its only new products were those that were more likely to cannibalize existing sales than boost the average ticket size, and even these new offerings did little to expand the company beyond a saturated and shrinking cupcake market. The company was executing its existing offerings well, but competition and changing consumer priorities were quickly shifting its context. In July 2014, as same-stores sales continued to decline and costs climbed, the company – by then the world’s largest cupcake company – failed.

|

2. Designing solutions that do not resonate. Another danger presented by institutional blindness is creating a product or service that does not fit with

a customer’s lifestyle or satisfy what she is trying to get done. For instance, IKEA almost completely botched its first entry into the U.S. market. As a former executive noted, “We got our clocks cleaned in the early 1990s because we really didn’t listen to the consumer.”3 U.S. consumers struggled to buy beds (which were measured in centimeters rather than standard sizes) and kitchen cabinets (which were too small for U.S. housewares). |

“We got our clocks cleaned in the early 1990s because we really didn’t listen to the consumer.” |

They also were buying vases to drink out of because the glassware offered was simply too small. While IKEA transformed its U.S. product lines and recovered, its initial oversights nearly cost the company a crucial growth market. It sounds basic, yet the fault consistently recurs: companies think they understand their customers when they really don’t.

3. Repeating the mistakes of others. No company can be an expert in everything. Yet companies often choose to go it alone instead of reaching out to other companies, academics, and consumers to help them understand key issues. In our emerging markets work, we see company after company rack up serious losses before they realize that they simply don’t understand the environment and are at a loss to make sense of the interplay between different domestic groups, businesses, and officials and their agendas. In these situations, local groups or other noncompetitive multi-nationals, who know the landscape, can provide invaluable help in negotiating the complexities of the environments and dealing with the inevitable impediments that confront foreign operators. To take one example, the U.S. military spent billions of dollars in Afghanistan investing in development programs like primary education and large scale infrastructure projects with few results. Not understanding how decision-making takes place below the national level, money was continuously funneled into shady local government structures that benefited political entrepreneurs and well-connected businessmen. Once military commanders began talking to local and international aid groups who had been working at the sub-national level in Afghanistan for decades, they began shifting their investment away from the official government representatives to the local community leaders, with vastly improved outcomes. Had the commanders talked to grassroots groups from the start, they would have certainly saved a tremendous amount of time, money, and frustration.

3. Repeating the mistakes of others. No company can be an expert in everything. Yet companies often choose to go it alone instead of reaching out to other companies, academics, and consumers to help them understand key issues. In our emerging markets work, we see company after company rack up serious losses before they realize that they simply don’t understand the environment and are at a loss to make sense of the interplay between different domestic groups, businesses, and officials and their agendas. In these situations, local groups or other noncompetitive multi-nationals, who know the landscape, can provide invaluable help in negotiating the complexities of the environments and dealing with the inevitable impediments that confront foreign operators. To take one example, the U.S. military spent billions of dollars in Afghanistan investing in development programs like primary education and large scale infrastructure projects with few results. Not understanding how decision-making takes place below the national level, money was continuously funneled into shady local government structures that benefited political entrepreneurs and well-connected businessmen. Once military commanders began talking to local and international aid groups who had been working at the sub-national level in Afghanistan for decades, they began shifting their investment away from the official government representatives to the local community leaders, with vastly improved outcomes. Had the commanders talked to grassroots groups from the start, they would have certainly saved a tremendous amount of time, money, and frustration.

|

“Institutional blindness also leads organizations to make substantial investments of human and financial capital without being fully apprised of the risks.” |

4. Over-investing in risky situations. Institutional blindness also leads organizations to make substantial investments of human and financial capital without being fully apprised of the risks. Consider the confident push by Britain’s Cadbury into Eastern Europe in the 1990s. As communist regimes began to collapse, global consumer goods companies rushed to build large plants to bring their products into these newly accessible markets. Attracted by Poland’s large population and relatively liberal legislation with respect to foreign businesses, Cadbury decided that there was little need to work with or acquire a local company; it could go at it alone. In 1993 the company decided to invest £20 million to build its own chocolate factory and sales network in southwest Poland.

|

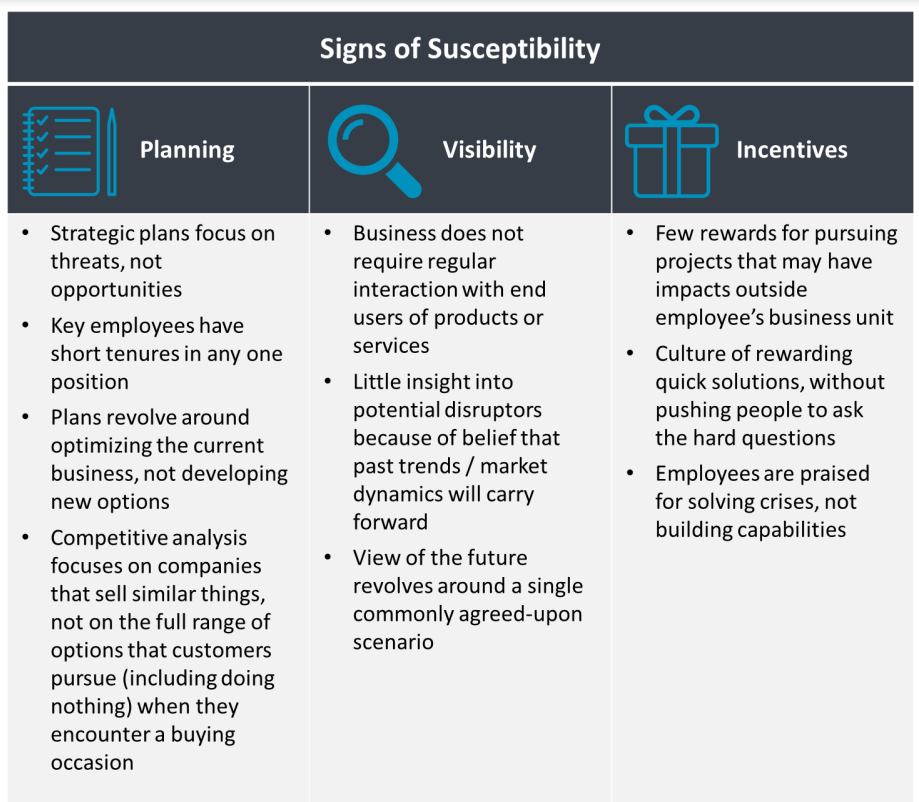

After 3 years Cadbury was making a modest profit, butit continued to struggle to gain market share in a rapidly-growingmarket. Cadbury ultimately realized, after much expense, that the local leader, Wedel, was offering consumers what they really liked – a less sweet, less milky chocolate. And for the minority of customers who did prefer sweet milk chocolate, the established local Milka brand already had a loyal following. In 1998, Cadbury was forced to reverse direction and acquire Wedel and its 23% market share. Cadbury deprioritized its own brands, ultimately using its resources to promote Wedel products – a strategy that Cadbury still uses today.4 While these four dangers often seem obvious in hindsight, blindness tends to creep in through the gradual accumulation of small, seemingly innocuous behaviors. Through our research, we have identified common indications that a company may be blinding itself. People who notice the warning signs should force their teams to stop, evaluate which quadrants of blindness may be afflicting their organizations, and determine whether their teams can use the remedies presented in the next section to eliminate blind spots.

DEFEATING INSTITUTIONAL BLINDNESS

“There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

– Donald Rumsfeld, U.S. Department of Defense news briefing, February 12, 2002

Most people will agree that there is uncertainty about the future, and companies will likely have differing perspectives on how the future will unfold. As Secretary Rumsfeld’s quote articulates, however, organizations can be blind to the future in different ways. Sometimes blindness comes in the form of an unchecked assumption while crafting a business case. Other times it appears as a complete lack of knowledge regarding how a customer or market will react to a particular move. However uncertainty manifests, each category of blindness can be managed by applying one of the best practices used by top innovators and forward-thinking companies.

The first quadrant of blindness – the known knowns – represents instances in which companies have done research and confirmed their assumptions with data. At first glance, this hardly seems like blindness at all. The problem, however, is that companies tend to over-rely on old data and past experiences. Much in the way that Crumbs hoped to succeed simply because it was an early entrant into the gourmet cupcake realm, companies regularly fail to look for answers beyond the core business. Managing blindness in this quadrant requires challenging past assumptions to ensure that they still hold true. This means that project teams must understand and question the ingoing hypotheses of stakeholders from other business units. It requires teams to frame up multiple views of the future and to ask difficult questions about each one, even knowing that management rewards answers, not questions. Teams that succeed in challenging truths do so by investigating broader views of competition, adjacent markets for expansion, and new potential business models.

|

When we helped a national retailer refine its eCommerce strategy, there was a widely-held belief throughout the organization that customers were reluctant to shop online and have the company’s products shipped to their homes and left outside. Multiple plausible rationales supported the belief, such as fears of stolen packages or a perceived lack of freshness with the company’s more perishable products. Convinced that there was more to the story, the strategic planning team asked us to take a closer look at the assumption. A survey of thousands 6 of customers revealed that only 4% of the company’s target customers were uncomfortable shopping for the company’s products online and having the goods shipped to their homes and left outside.

|

“In seeking to verify assumptions, companies often overlook the value of getting truly close to their customers.” |

After years of shopping online for other goods, those customers who did have concerns about stolen packages, for example, had largely developed workarounds. They often had packages shipped to their offices or left with neighbors. By challenging an outdated assumption, the strategic planning team was able to pave the way for substantial investments in the company’s eCommerce capabilities, ultimately enabling the company to capture substantial spend as online shopping in the category grew at a remarkable rate.

The second quadrant of blindness – the known unknowns – contains instances where companies have laid out their view of the future, but they recognize that there are key assumptions that need to be tested. In seeking to verify assumptions, companies often overlook the value of getting truly close to their customers. When one of us worked at the pan-African cellular network Celtel in the early 2000s, the company was rapidly penetrating the market for upper-income subscribers. Yet the business model it had imported from Europe, based on prepaid airtime loaded up through scratchcards, turned out to be an impediment to growth in the critical down-market segment. Once Celtel closely listened to the needs of the company’s subscribers and partners, it understood a big reason why. Scratchcards cost about 5 cents to produce, and to make their sale economic the lowest value scratchcard was sold for about $5. This was a large amount of money for some people to scrape together. Moreover, small shops in poor townships did not carry many of the scratchcards due to the inventory cost and concerns about theft. Stockouts were common. Celtel reinvented that business model, allowing the company to become one of the first networks worldwide to roll out over-the-air top-ups of airtime, whereby customers would purchase as little as $1 of airtime through a remote, scratchcard-less transaction. Business boomed. As Celtel learned, the solution lies in conducting real-world, open-ended research from beyond the confines of a boardroom. The company needed to set aside pre-conceived notions, instead looking for the behaviors and contexts that are truly surprising

The second quadrant of blindness – the known unknowns – contains instances where companies have laid out their view of the future, but they recognize that there are key assumptions that need to be tested. In seeking to verify assumptions, companies often overlook the value of getting truly close to their customers. When one of us worked at the pan-African cellular network Celtel in the early 2000s, the company was rapidly penetrating the market for upper-income subscribers. Yet the business model it had imported from Europe, based on prepaid airtime loaded up through scratchcards, turned out to be an impediment to growth in the critical down-market segment. Once Celtel closely listened to the needs of the company’s subscribers and partners, it understood a big reason why. Scratchcards cost about 5 cents to produce, and to make their sale economic the lowest value scratchcard was sold for about $5. This was a large amount of money for some people to scrape together. Moreover, small shops in poor townships did not carry many of the scratchcards due to the inventory cost and concerns about theft. Stockouts were common. Celtel reinvented that business model, allowing the company to become one of the first networks worldwide to roll out over-the-air top-ups of airtime, whereby customers would purchase as little as $1 of airtime through a remote, scratchcard-less transaction. Business boomed. As Celtel learned, the solution lies in conducting real-world, open-ended research from beyond the confines of a boardroom. The company needed to set aside pre-conceived notions, instead looking for the behaviors and contexts that are truly surprising

The third quadrant of blindness – the unknown knowns – consists of instances in which key data exists, but teams have not asked the right questions that would lead them to that information. This often happens within teams having homogenous backgrounds. Collaboration with other departments, experts, and entities allows teams to gain perspectives that are otherwise lacking. Celtel’s field sales staff knew the issues that scratchcard retailers were having, but they were several layers of management removed from the expatriates running the business. Teams can reach out to market experts, academics, non-competitive companies, their own employees, and consumers to answer specific questions they may have – and they need to do so in a routine way that is not unduly bottlenecked by limited functions such as a market research or business development team. Sending team members to conferences, inviting experts to speak with your teams, and creating innovation competitions are all ways to bring in valuable pieces of knowledge without expending substantial resources or jeopardizing trade secrets. Pearson – a leading education company and book publisher we worked for – has been questioning what the future of education will look like as the world becomes heavily Internet-focused.

The company launched the Pearson Catalyst for Education program in 2013 to accelerate its push into digital learning. The goal was to bring in expertise from promising startups and to help Pearson explore how new technologies can lead to better educational products. In two years, Pearson worked with 15 companies, two of which became official technology partners for Pearson. Through its work with the startups, Pearson has been able to expose its staff to a wider range of viewpoints, while also finding partners to help solve targeted challenges. For example, Catalyst startups have helped staff better understand how teachers evaluate student learning, what gamification efforts have proven successful, and how much of a role self-paced learning can play in different forms of education. By looking beyond its own core group of researchers and editors, the Catalyst team helped the organization spot opportunities for growth along entirely new dimensions

The fourth and final quadrant of blindness – the unknown unknowns – involves instances where companies do not know how the future will unfold or how a market will react. In these cases, existing data simply does not provide the required answers. Resolving the leftover uncertainty requires companies to conduct experiments and build prototypes to better understand how offerings will fare in the real world. Teams need to focus their limited resources on fast, cheap tests that can answer specific questions. Sometimes these tests can be as simple as showing customers a brochure for a potential product, or surveying existing markets to determine whether stores of similar size have opened there and done well. The goal is to take a rigorous and scientific approach to determining the validity of ingoing hypotheses, especially if responding to those hypotheses allows the team to reduce the risk of proceeding. As risk is reduced, experiments can be bigger in size, ultimately leading to early-stage pilots. These tests also allow teams to capture feedback that can be used to enhance future iterations of the offering. Teams can learn what customers liked or disliked about an offering, where they had questions, and where they offered suggestions.

Consider a large drug company we worked with that was evaluating whether to launch tools for home monitoring of a chronic disease that it treated. The organization had validated that home monitoring would produce valuable data and that the potential tools had good reliability. The team tasked with deciding how to advance the initiative started out with a small test, sending the monitoring tools home with potential users. Many patients lost the equipment, put it on upside-down, or quickly stopped using it because monitoring wasn’t part of their normal routine. When they brought the equipment in to physicians, the doctors declined to download data from the devices – they were already short of time for the office visit, and the data analysis wouldn’t be compensated. The team quickly realized that its challenge wasn’t with the technology, but with changing human behaviors and incentives. That insight completely changed the company’s approach to the project.

CONCLUSION

The future may not be clear, but companies don’t need to sit in handcuffs until uncertainties resolve themselves. Leading an organization to success requires understanding how institutional blindness can arise, what types of blindness exist, and what actions can combat each form of the disease. Each form of blindness requires teams to critically assess what they think they know, approach problems from multiple viewpoints, and integrate real customer insights into their final offerings. By focusing on these core tenets – and being both flexible and cautious about how the future is approached – companies can prepare for the inherent uncertainties of what’s to come.

The fourth and final quadrant of blindness – the unknown unknowns – involves instances where companies do not know how the future will unfold or how a market will react. In these cases, existing data simply does not provide the required answers. Resolving the leftover uncertainty requires companies to conduct experiments and build prototypes to better understand how offerings will fare in the real world. Teams need to focus their limited resources on fast, cheap tests that can answer specific questions. Sometimes these tests can be as simple as showing customers a brochure for a potential product, or surveying existing markets to determine whether stores of similar size have opened there and done well. The goal is to take a rigorous and scientific approach to determining the validity of ingoing hypotheses, especially if responding to those hypotheses allows the team to reduce the risk of proceeding. As risk is reduced, experiments can be bigger in size, ultimately leading to early-stage pilots. These tests also allow teams to capture feedback that can be used to enhance future iterations of the offering. Teams can learn what customers liked or disliked about an offering, where they had questions, and where they offered suggestions.

Consider a large drug company we worked with that was evaluating whether to launch tools for home monitoring of a chronic disease that it treated. The organization had validated that home monitoring would produce valuable data and that the potential tools had good reliability. The team tasked with deciding how to advance the initiative started out with a small test, sending the monitoring tools home with potential users. Many patients lost the equipment, put it on upside-down, or quickly stopped using it because monitoring wasn’t part of their normal routine. When they brought the equipment in to physicians, the doctors declined to download data from the devices – they were already short of time for the office visit, and the data analysis wouldn’t be compensated. The team quickly realized that its challenge wasn’t with the technology, but with changing human behaviors and incentives. That insight completely changed the company’s approach to the project.

CONCLUSION

The future may not be clear, but companies don’t need to sit in handcuffs until uncertainties resolve themselves. Leading an organization to success requires understanding how institutional blindness can arise, what types of blindness exist, and what actions can combat each form of the disease. Each form of blindness requires teams to critically assess what they think they know, approach problems from multiple viewpoints, and integrate real customer insights into their final offerings. By focusing on these core tenets – and being both flexible and cautious about how the future is approached – companies can prepare for the inherent uncertainties of what’s to come.

HEADQUARTERS | 50 FRANKLIN STREET | SECOND FLOOR | BOSTON, MA 02110 | UNITED STATES | TEL. +1 617 936 4035

New Markets Advisors © 2023 - Terms of Use - Privacy Policy