|

For many years now we’ve seen the dangers of defining your business too narrowly. Think about Borders, which pioneered the book megastore model. Rather than using the Internet’s rise to consider how new technologies or business models could allow it to better satisfy customers’ jobs to be done, it defined itself as a bookseller. When times got tough, it doubled down on trying to sell more of the items its customers happened to be buying — books, CDs, and DVDs. It last turned a profit in 2006 before ultimately declaring bankruptcy and closing its doors in 2011. Online retailer Amazon now reigns supreme in the space. Defining your competition narrowly creates the same results. Blockbuster focused its attention on what it deemed to be the real competition — companies like Hollywood Video. It was certainly aware of Netflix (the company that ultimately disrupted the industry), but turned down an opportunity to buy it for a mere $50 million back in 2000. Blockbuster determined that Netflix was a “very small niche business” occupying a small corner of the market that mattered little to the giant. Over time, Netflix’s offering improved, the company moved up-market, and it redefined the way customers thought about video rentals. In addition to stealing market share, Netflix essentially mooted one of Blockbuster’s primary forms of revenue. In the very year that Blockbuster decided not to acquire Netflix, the company made a staggering 16% of its revenues from late fees — a concept that ceased to exist as Netflix changed the game. Interestingly, while both Amazon and Netflix slayed incumbent behemoths in their respective industries back in the 2000s, those disruptors are now competing with each other, even though they operate in seemingly different industries. But competition can no longer be defined in the traditional sense (i.e., those who happen to be selling the same goods or services that you’re selling). Rather, companies compete with anyone else who can satisfy the jobs that customers are trying to get done in their lives. They compete with businesses that can cause customers to spend their finite resources somewhere else. The Snickers bar in the checkout aisle competes not just with other candy bars, but also with the smartphone app that’s diverting the supermarket customer’s attention and obviating the need for an impulse purchase. Nike competes with other shoe makers such as Adidas and New Balance, but it is also in indirect competition with other products that offer customers a way to express themselves.

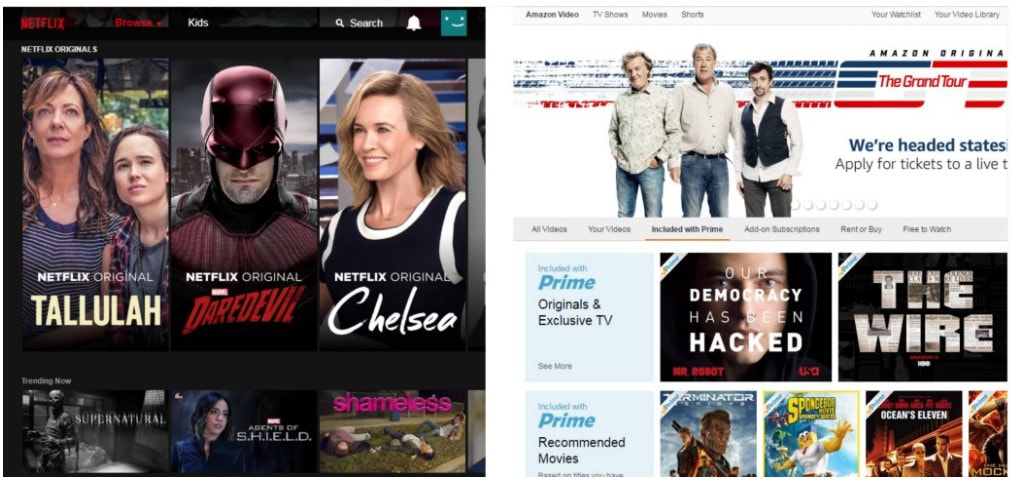

In this case, Amazon and Netflix are offering products that do look fairly similar, at least in some respects. Netflix offers a subscription to a library of movies and TV shows for around $100 per year. At a similar price point, Amazon offers its Prime membership, which, in addition to giving Amazon shoppers free two-day shipping, also gives members access to Prime Video — a digital collection of movies and TV shows. Now sure, Netflix could argue that Amazon is still a relatively small player in the video streaming industry. It could argue that Prime Video has a smaller selection of videos, less precise data about what users like, less advanced tools for categorizing and recommending new videos, and less established relationships with other industry players. It could argue — much as Blockbuster did some fifteen years ago — that Amazon is really more of a niche player in the industry, whose focus is really on retail. But Netflix would be foolish to do so. Ironically, the fact that Amazon’s primary focus is in another industry is perhaps what should worry Netflix the most. First, Amazon can worry less about its margins with respect to Prime Video because it’s not a core source of revenue for the company. Amazon’s primary sources of revenue are its core retail business and Amazon Web Services. Amazon doesn’t need to worry about the costs of licensing content or marketing Prime Video. Second, Amazon has a huge incentive to build interest in Prime Video. According to Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, Prime Video makes individuals more likely to pay for Amazon Prime and to renew their Amazon Prime memberships. Amazon Prime members, in turn, spend more than the average non-Prime customer. By creating a better Prime Video offering, Amazon is able to sell more books or shoes or other goods. Amazon has a real incentive to see Prime Video succeed. It may well turn out that Netflix and Amazon learn to live together in harmony. Customers may ultimately choose to have both an Amazon Prime membership (complete with its Prime Video benefits) and a Netflix subscription. But as Prime Video continues to creep up-market, steadily increasing in performance along the dimensions that matter most to consumers (e.g., better selection, the ability to download shows for offline viewing), Netflix certainly has something to worry about. Given its own status as an industry disruptor, we can be sure that Netflix is looking beyond just incremental improvements to its subscription offering to ensure its long-term health. Learn more To learn more about how understanding customers’ jobs to be done can help companies think differently about competition and preemptively fend off potential disruptors, check out the page for our new book Jobs to be Done: A Roadmap for Customer-Centered Innovation. We offer a detailed look at Jobs to be Done thinking, a sample chapter, and several tools and frameworks that we feature in the book. Comments are closed.

|

8/15/2016