|

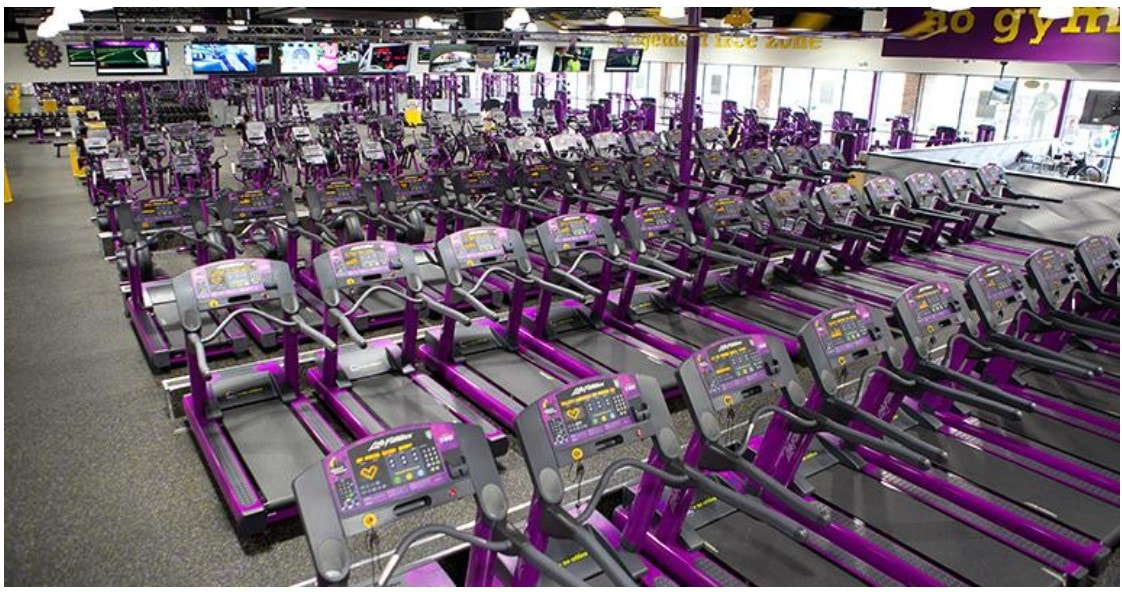

The innovations that most capture our interest—and that of “innovations of the year” listicles—also tend to capture our imagination: self-driving cars, personal robots, pizzas delivered by drone. These innovations are daring. They redefine our technological boundaries. They inspire us with their sparkle and shine, even if we don’t really understand blockchain or ever plan on mounting a bendable TV screen on our living room wall. Even when the product itself is unattainable, impractical, or downright unaffordable, the mere idea can be a source of entertainment. This is the country that first put a man on the moon, after all; an aspirational view of innovation is hard-coded into the American psyche. Is it any wonder that we love reading about leisure rockets from SpaceX and a military base on the moon? But let’s contrast this picture of glistening technological advancement against the portrait of the average American. There, of course, is no singular average Joe, but the indicators overall are troubling. Income for the bottom 90% has seen little to no growth in the past 30 years.[1] At a scant 3%, the personal savings rate is at an all-time low.[2] Sixty percent of Americans don’t have enough savings to cover a $500 emergency.[3] Student debt is up, and retirement savings are down. The average American is worse off than we’d like to admit, and worse off than our technological innovations would seem to suggest. Which means there is a mismatch: What is a $1,000 smartphone going to do for the 78% of Americans who don’t feel financially secure?[4] 90% of our country are not super-premium buyers. Where is the game-changing, category-creating innovation for them? And why is it missing? In search of affordable innovations Let’s be clear: “affordable innovations” are not just cheaper, watered-down versions of upscale products, like the Tesla Model 3 or the iPhone SE. Those incremental improvements are fine, but they aren’t transformational innovations, and they surely leave users wanting more. Nor are they products that have been stripped down to hardly anything at all, like Ryanair, whose infamous push for cost-cutting led it to consider charging for bathroom use.[5] Gritted teeth and accusations of greed are not the end goals. 90% of our country are not super-premium buyers. Where is the game-changing, category-creating innovation for them? And why is it missing? Rather, what we’re calling for are low-cost solutions that surprise, empower, and create a great customer experience. This means fundamentally rethinking products and services to be affordable from the outset, not just creating low-cost sequels. Planet Fitness is a great example. The average cost for a gym membership in the U.S. is about $52 per month. Planet Fitness charges less than a fifth of that.[6] Admittedly, there’s a lot that Planet Fitness doesn’t offer—like towels, Zumba classes, daycare, and an extensive free weights area. But Planet Fitness isn’t maligned by its members; in fact, it ranks first in customer satisfaction, even ahead of luxury giants like Equinox.[7] What we’re calling for are low-cost solutions that surprise, empower, and create a great customer experience. This means fundamentally rethinking products and services to be affordable from the outset, not just creating low-cost sequels. How does Planet Fitness pull that off? Instead of engaging in the “race to the top” for expensive perks, Planet Fitness focuses on what first-time gym-goers and casual exercisers need: rows and rows of cardio equipment that they never have to wait for, and no pressure or intimidation from personal trainers and grunting meatheads. The result is a new kind of gym, one that differs in both layout (mostly treadmills and ellipticals) and business model (no revenue from personal training). It is also supremely affordable and approachable for the 81% of Americans who don’t belong to a health club.[8] The low-cost innovation tide lifts all boats Every industry needs a Planet Fitness—with creative new offerings at a radically lower price, tailored for mainstream Americans. But this kind of innovation, which we term “costovation,” isn’t happening often enough, nor is it receiving the attention it warrants. This is problematic because the vast majority of Americans don’t just prefer less expensive products—they need them. Paychecks have largely stayed the same over the past two decades, while the cost for essentials like healthcare and education have skyrocketed.[9] Even certain leisure items like hotel rooms have steadily become more expensive, nearly doubling from $67 in 1995 to $124 in 2016.[10] These price increases fly in the face of continuously decreasing manufacturing costs and increasing productivity. Could rising labor costs be contributing to the price growth? Perhaps a bit, but they shouldn’t take all the blame: the federal minimum wage has been stagnant at $7.25 since 2009. Tack on rising interest rates and a looming trade war, and everyday items are threatening to become even more expensive. With our parade of fancy gadgets and tech-enabled-everything, are we being tone-deaf to the needs of the everyday American? But lower- and middle-income Americans wouldn’t be the only beneficiaries of a shift in focus: we all have something to gain from simpler approaches to what has been made complex and costly. Americans of all incomes have shopped at stores like Trader Joe’s and IKEA, which have made radical leaps in costs by boldly limiting selection and engineering new ways to pack furniture. Some people may not need the lower prices, but they certainly appreciate them, and they come back again and again because those retailers provide great customer experiences in other ways. Moreover, new low-cost approaches are an insurance policy. If all our innovation efforts are focused upmarket, how ready are we to weather the next macroeconomic downturn? Consider this: the average period of expansion between recessions is about 5.5 years. It has been 10 years since the financial crisis, and the U.S. is entering the longest period of economic expansion in its entire history. Cue the warning sirens. By the time a downturn strikes, it will be too late to develop, test, and scale the low-cost approaches that the market will demand and that companies will require. If all our innovation efforts are focused upmarket, how ready are we to weather the next macroeconomic downturn? How have we overlooked costovation for so long? A major culprit responsible for the disconnect between recent innovations and our American demography is our societal obsession with the latest and the greatest. That habit runs deep. As a country, we are drawn to technological glamour like mosquitoes to a light. We can all name Steve Jobs because he created the supercomputer in your pocket. But how many of us can identify Malcolm McLean, who invented the shipping container? It is because of McLean’s humble but mighty standardized shipping container that an iPhone costs what it does, having enabled cheap transport from China across seas, mountains, and plains. The shipping container invention impacts each of us every day, but it’s not stylish. And so it goes underrecognized. CEOs aren’t immune to that thinking. Companies are repeatedly seduced by moonshot projects—the ones that garner free PR and attract talented workers, but which only benefit a small segment of people. Low-cost and low-tech innovations don’t easily garner headlines that the CEO can brag about to the board, even though those innovations could have tremendous impact on both the company and on the mainstream American people. Companies also like to measure their efficiency by pointing to financial ratios. But these ratios miss what is less visible: the large markets that companies are ignoring in pursuit of ever pricier products. These new markets may be somewhat less profitable to serve, yet the dollars at stake are vast and the ultimate profit potential is robust. In the end, banks accept deposits in dollars, not ratios. There is ample room for disruption in industries where the major players are only looking upwards, and companies fixated on the metrics can miss the underlying success those metrics are supposed to indicate. Finally, as employees of these companies, we gravitate toward the standout, glamorous, highly-visible projects. These are the efforts that make our resumes sparkle and our reputations legendary. We would do well to salute the unsung champions who bravely re-think costs, creating the shipping containers, simple small stores, flat-packed furniture, and other game-changing innovations that alter the world every bit as much as the glitzy baubles we tend to hype. We gravitate toward the standout, glamorous, highly-visible projects. These are the efforts that make our resumes sparkle and our reputations legendary. Making radical leaps in costs, alas, takes time. And with shareholders clamoring for short-term gains and quarterly returns, there is little patience for the timeframes it takes to create and prove big market-changing innovations. Yet, in a recession their patience will be even thinner. There is never a perfect time to innovate, just difficult and more difficult ones. This is a call to the would-be Elon Musk’s of the world: lavish the same attention on clever solutions that make innovation affordable. There is a lot of sizzle in that, if we choose to see it. Jennifer Luo Law is co-author of Costovation: Innovation That Gives Your Customers Exactly What They Want—And Nothing More (HarperCollins Leadership, 2018), which was named a top ten business book of 2018 by Canada's leading newspaper, The Globe and Mail. [1] Author’s analysis using data from the National Bureau of Economic Research Consumer Finance Survey [2] Emmanuel Saez & Gabriel Zucman, "Wealth Inequality in the United States since 1913: Evidence from capitalized income tax data," National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, 2014 [3] McGrath, Maggie, 63% of Americans Don’t Have Enough Savings to Cover a $500 Emergency, Forbes 2016 [4] Prudential, Financial Wellness Consumer Research, 2016 [5] Scott Mayerowitz, “Paying to Pee: Have the Airlines Gone Too Far?” ABC News, 13 April 2010 [6] Planet Fitness 2016 Annual Report [7] “Health and Fitness Centers Get Lift From Improving Customer Satisfaction, J.D. Power Finds,” J.D. Powers, 14 June 2017 [8] “2017 Health Club Consumer Report,” International Health, Racquet & Sportsclub Association [9] Christopher Ingraham, “The stuff we really need is getting expensive. Other stuff is getting cheaper,” Washington Post, 17 Aug 2016 [10] “U.S. Lodging Industry Overview,” Cushman & Wakefield, March 2017 Comments are closed.

|

2/5/2019