|

Consider this oddity. A new Conference Board survey has revealed that growth has become the number one priority of large company CEOs. Yet typical large company CEOs, and even the people two levels beneath them, have not specified basic growth priorities for what the firm could do in new areas. Why?

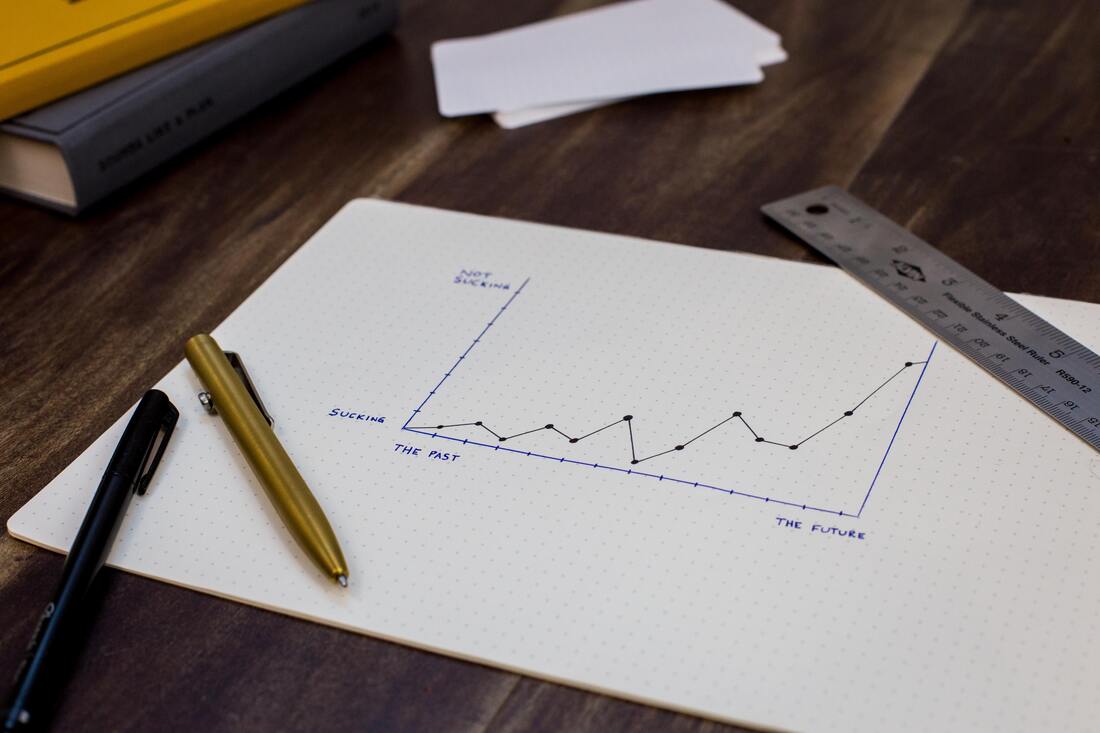

To take one example, a client I recently visited has spent millions on consulting and market research to probe areas adjacent to its core business, but the people tasked with leading the charge still aren’t sure about what top management really wants. So they have invested heavily in developing detailed business cases for new ventures, only for executives to say that some parameter just won’t work for them. These same executives do find the time to ponder how to increase prices, take share from competitors, and acquire companies — all basically zero-sum activities — yet they have not specified the growth priorities for how the firm might create new markets, which are positive-sum activities and have powered the greatest business successes of the past 150 years (Standard Oil, AT&T, Ford, IBM, Fidelity, Microsoft, GE Capital, Facebook, and many more). The nub of the problem is that corporate planning typically takes place in a world of clear facts and options. Executives can choose to invest in well-detailed initiatives with reasonably predictable results. Slide decks with oceans of data make management comfortable with their decisions. Progress in achieving the forecast results can be assessed regularly, and employees can be incented accordingly. This sort of environment meshes well with the way executives govern corporations — they can receive occasional updates and ask sharp questions. But new markets are totally different. The facts can be fuzzy and contradictory, options are innumerable, and the ultimate destination unpredictable. Management cannot review progress against plans, because plans become rapidly outdated. Employee performance is difficult to measure. So, executives forgo creating over-arching plans for new markets. Instead they ask the middle tiers of the company to propose new ventures, which they will then consider one by one. These proposals are concrete and readily grasped, therefore discussion can be specific. It makes great sense for the executives, but leads to tremendous confusion down below. Because the executives have not clearly stipulated their priorities, underlying divergences among them are not discussed in a straightforward way. Instead, their differing views are surfaced through varying opinions about a venture. “Bob, this will alienate a big customer of ours.” “Mary, the long-term growth potential is much greater than sales from that customer.” And so on. If the Executive Committee were the Supreme Court, it would justify its decisions with a clear set of principles that could be used to guide future cases. But the Executive Committee is too busy to do that, so the process feels more like traffic court. “We won’t invest in that business. Next case!” What can be done? A little effort goes a long way. Rather than scope out a plan in detail, with financial expectations and a ranking of potential markets, set out key principles. What are the criteria by which management will judge ideas? What would be out of scope? What historical or current examples provide a potential template to follow? What aspects of the core business must be sacrosanct (e.g. avoid sales channel backlash), and which can be stretched? This sort of guidance can be created during a single well-planned meeting and can be extraordinarily helpful. Then devise a governance process that looks less like a big company and more like a venture capitalist. Have frequent but brief meetings with the team to jointly solve problems, understand priorities, and share views. Ask for little data — which is often backward-looking — and more about trends. Establish a couple of key things for the team to work on at any one time, and do not overload people with mandates. Don’t aim for executional excellence (expensive, time-consuming, and often directed at the wrong target), but for fast learning and iteration. These sorts of behaviors are unfamiliar in big corporations, but they are not inherently difficult. By investing modest amounts of time in new sources of growth, executives can live up to the aspirations they express in surveys. Story by Steve Wunker. Comments are closed.

|

4/23/2011