|

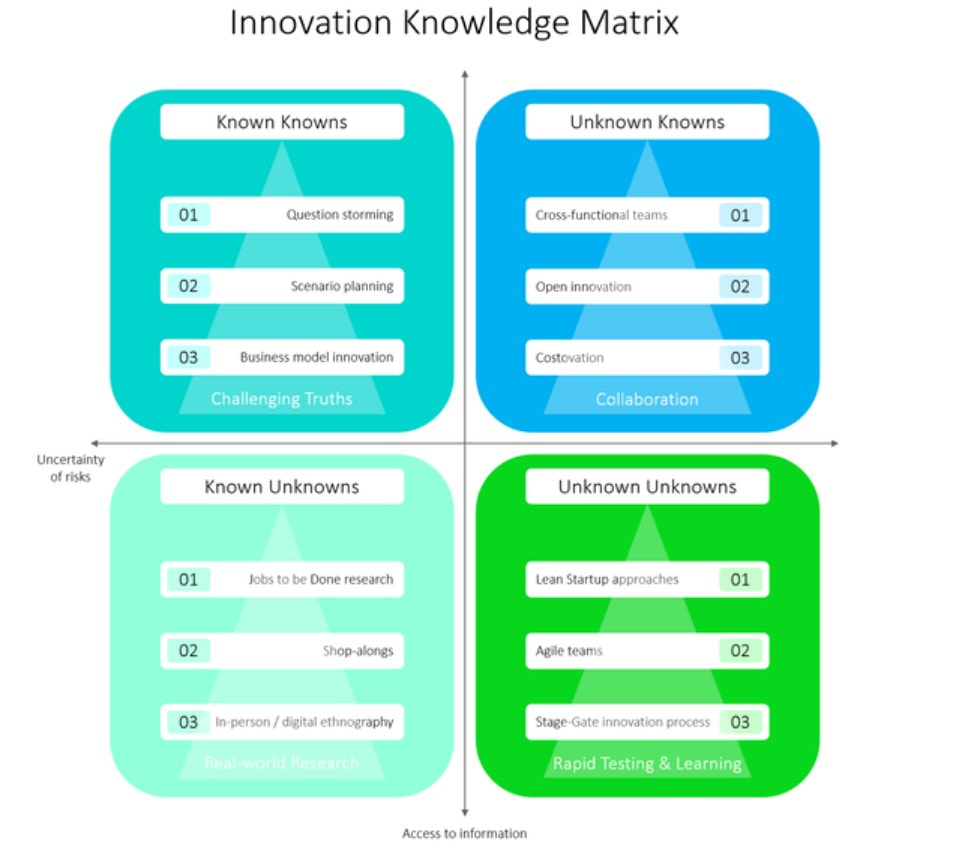

By Dave Farber A few years ago, I developed a framework for finding, testing, and mitigating risks and uncertainties in periods of volatility. The idea came out of a recent survey of U.S. CEOs, which showed that 86% believed that advances in technology would transform their businesses in the next five years. It also showed that 60% of respondents believed that new market entrants would threaten their growth prospects. Even in calm times, fear of the unknown was top of mind for corporate leaders. As COVID-19 (the novel coronavirus) disrupts lives, businesses, and societies at large, those uncertainties are even more prevalent. Companies are struggling to understand how their supply chains will be disrupted, how their customers will behave (both now and once a “new normal” is established), and how the competitive landscape will evolve amidst the changes that occur. Panicked decisions are rarely good ones. Indecision can be equally dangerous. Making strong strategic choices for the future requires asking the right questions, getting all available information on the table, quickly testing the uncertainties that remain, and thinking through the implications of those choices across the different futures that could potentially unfold. To that end, I’m sharing the Innovation Knowledge Matrix (IKM) — a tool for finding and addressing the uncertainties that could impact your business. The challenges of operating in uncertainty In a 2002 press briefing, then Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld made headlines talking about the difficulties in addressing the unknown unknowns — the things that we don’t know we don’t know. Secretary Rumsfeld’s remarks highlighted a phenomenon that exists as much in business as it does in politics or the military. Quite simply, there are different ways in which companies might not know how the future will unfold, and each of those contexts requires different tools for getting the information you need. While there are many different systems for categorizing risks (e.g., by business function, by timing), the IKM creates a broader segmentation of unknowns that divides risks and assumptions along two dimensions: your awareness of those risks and unchecked assumptions, and your current access to the information that addresses them. Known knowns. The first category of unknowns reflects instances in which companies have done research in the past and they have the data to answer their questions; they know what the risks are, and they have their answers. At first glance, it seems like there aren’t any unknowns in this scenario. The problem is that companies exploring familiar spaces tend to over-rely on outdated research and past experience, regardless of what else may have changed. This means that their pursuits could be relying on inaccurate information, and it also means that they may be missing new market opportunities that hadn’t been considered in the past. When Crumbs Bake Shop launched in 2003, there were only three bakeries devoted to cupcakes in the U.S. The company expanded a little, and it relied on the success of its existing stores as proof that it could orchestrate a massive expansion. Unfortunately, Crumbs devoted little attention to growth opportunities for its stores beyond trying to replicate its existing model in new locations. Its only new products were those that were more likely to cannibalize existing sales rather than boosting average ticket sizes, and the company was left with a high-cost expansion in a heavily saturated cupcake market. Despite a few attempts to reorganize, the company ultimately closed all of its stores. Before pursuing such an aggressive expansion, Crumbs could have done several things to reduce its risk. The company could have run a question storming session to challenge its assumptions on why the expansion could succeed. That could have been combined with scenario planning to understand how its growth would be affected by external market changes. Refreshing its research would have highlighted competitive growth, and ideation sessions around business model innovation would have revealed opportunities to change with the times, including the addition of complementary products, a differentiated customer experience (e.g., Instragrammable “food museums”), or alternative channels to explore (e.g., on-demand delivery). Known unknowns. The second category exists where companies lay out a view of the future and recognize that there are key assumptions that need to be tested. Unfortunately, they don’t get to know their customers well enough, and they end up designing solutions that don’t resonate. Maybe they try to rely on transaction data rather than talking to customers. Or they ask customers what they want rather than understanding their jobs to be done. IKEA fell victim to this trap and almost completely botched its first entry into the U.S. market. As a former executive put it, “We got our clocks cleaned in the early 1990s because we really didn’t listen to the consumer.” While U.S. customers tried to shop at new IKEA stores, the experience was a struggle. Beds were measured in centimeters rather than standard U.S. sizes (e.g., Twin, Queen, King). Kitchen cabinets came in sizes that were too small to fit American housewares. Consumers were buying vases to drink out of because the glassware seemed comically small. The company revamped its product lines and recovered, but its lack of customer empathy almost cost the organization a crucial growth market. While IKEA understood the core job of its customers and some of the success criteria — to affordably furnish a new living space in a hurry — it lacked a closeness to its customers that was truly necessary. It could have joined consumers on existing shopping trips, gotten a view of what their homes and housewares looked like already, and determined what other jobs consumers were hiring home stores for. Unknown knowns. The third category consists of instances in which key data exists, but teams haven’t asked the questions that would lead them to the right information. Knowledge is siloed or teams focus on trying to generate the best possible solutions (which are highly valued by organizations) rather than spending sufficient time developing the right questions (which are often under-valued). One of the more common problems here is that companies end up repeating the mistakes that others have already made. In 2013, Target had a troubled entry into Canada when it marked up its prices in Canadian stores to account for its increased operating costs. Canadian customers — used to shopping in the U.S. — balked at the higher prices and refused to shop there. Teams didn’t need to look far outside their organization to find evidence that this could be a problem. J. Crew had made the same mistake in 2011. Retail may be a low-margin business, but Target could have explored other ways to cut costs and optimize its entry into Canada. Cross-functional teams, collaboration with those outside the organization, and Costovation audits — to determine where there are major cost drivers in a business — can all be useful ways to get valuable knowledge that project teams might not have on their own. Unknown unknowns. The final category of unknowns is the area of greatest uncertainty. It refers to instances in which companies don’t know how the future will unfold or how markets will react to new concepts. The answers don’t yet exist. Without resolving key unknowns, companies can end up over-investing in risky situations. In the 1990s, Cadbury made a confident push into Eastern Europe. Communist regimes were collapsing, and the company wanted to be a first-mover in these newly accessible markets. Cadbury quickly invested £20 million building a chocolate factory and its own sales network in Poland. But revenues were modest, and the company struggled to gain market share in a rapidly-growing market. It turned out that consumers in the market preferred dark chocolate over Cadbury’s milk chocolate. And those who did like milk chocolate were fiercely loyal to a local brand (Milka). After five years and heavy investments, Cadbury was forced to reverse direction, deprioritize its own products, and acquire another brand (Wedel) and its dark chocolate portfolio. Rather than investing in some quick in-market tests, where Cadbury could have quickly learned of consumers’ chocolate preferences, the company opted to make a large investment and test later. That was a costly mistake. Building a process that encourages test-and-learn experimentation and iterative design processes will help companies venture into the high-potential unknown-unknown spaces without investing too quickly and running headlong into unforeseen risks. The challenges of making complex decisions in periods or environments of uncertainty aren’t new. Companies have been dealing with them for decades. While COVID-19 makes us feel as though we’re living in chaos, blind spots have always existed. Innovators have been continuously developing new strategies that can help us find clarity in these uncertain times, mitigate risks, and set clear guidance for how to move forward. While times of discomfort may feel like a good time to stand still and see how things play out, others won’t. Times of trouble are when innovation is needed most. Dave Farber is a strategy and innovation consultant at New Markets Advisors. He helps companies understand customer needs, build innovation capabilities, and develop plans for growth. He is a co-author of the award-winning book Jobs to be Done: A Roadmap for Customer-Centered Innovation. Comments are closed.

|

3/25/2020